Standplaats Vlieland

Artist residency hosted by Into The Great Wide Open, Hi-Lo and Museum Tromp’s Huys

Standplaats Vlieland

My research on Vlieland focuses on the relationship between humans and nature in a landscape entirely shaped by the tides. The Wadden Sea shows us, every day, the cyclical character of the world: water recedes and returns, sandbanks appear and disappear, birds and people follow each other in temporary patterns. At the same time, this landscape is under pressure from human decisions: climate change, gas extraction, fisheries, tourism, and pollution alter its ecological balance. The Wadden Sea is always in motion, but that movement is not always self-evident or positive. By working with real-time tidal data from Rijkswaterstaat, I aim to translate these rhythms and transformations into an installation that not only embodies the cyclical nature of the Wadden but also makes the vulnerability of this ecosystem tangible.

For the next six weeks I will be living on the island, carrying out my research directly on site.

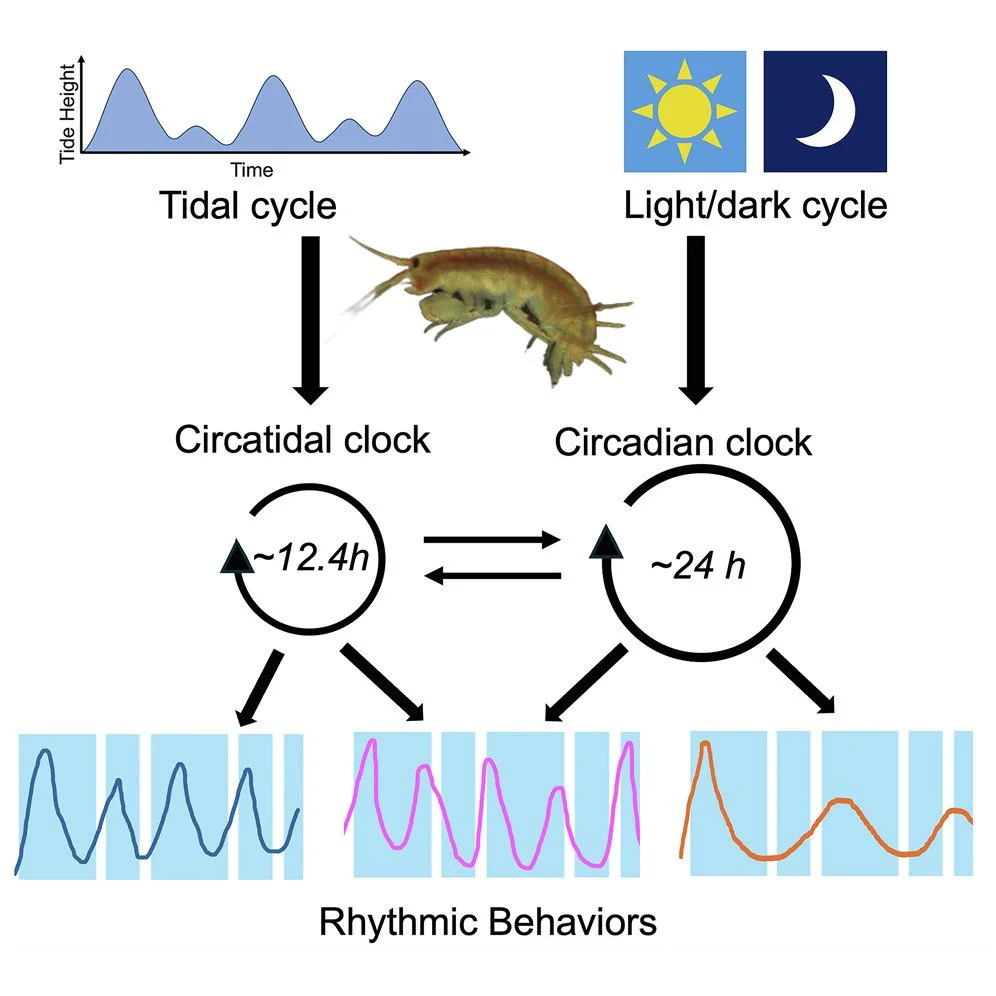

In humans, the biological clock mainly follows a circadian rhythm of about 24 hours, tuned to the cycle of day and night. This clock, located in the brain, regulates processes such as sleep, alertness, and hormone release. In marine animals like shrimp and cockles, however, there is also a tidal clock, which runs on the rhythm of the tides (around 12.5 hours). This allows them to adjust feeding or protective behaviors to changes in water levels. It shows how biological rhythms adapt to the specific environment of each species.

These observations have led me to consider the tide itself as a kind of clock. My aim is to create an installation that is guided by the circatidal cycle. The work will breathe with the sea, responding to forces beyond human control, and in doing so, propose another way of experiencing time: fluid, adaptive, and inseparable from the environment that sustains it.

Anthropocentrism places humans at the center, turning nature into backdrop and resource; a worldview driving both climate crisis and our growing sense of disconnection. Yet the tidal rhythms resist such separation: the flow of water reminds us that we are not apart, but always already entangled in larger forces.

Jellyfish embody an alternative way of being: they live almost indistinguishable from the water around them, ‘like water in water’. They suggest a mode of existence where the boundary between organism and environment dissolves, an image that contrasts sharply with human fantasies of separateness and control.

Running a first test with motors triggered by real-time waterlevels

And a first testmodel for a wave-mechanism

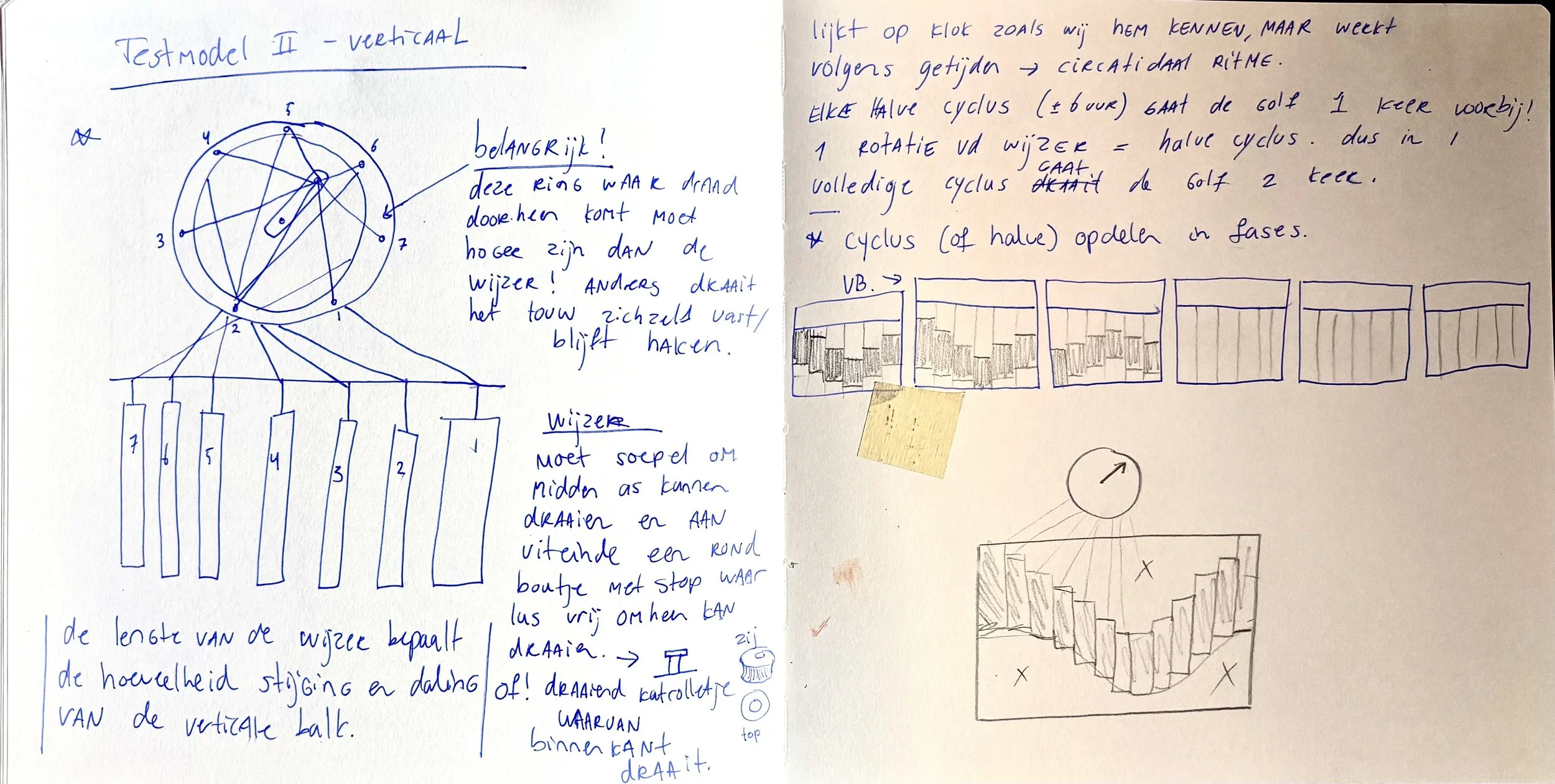

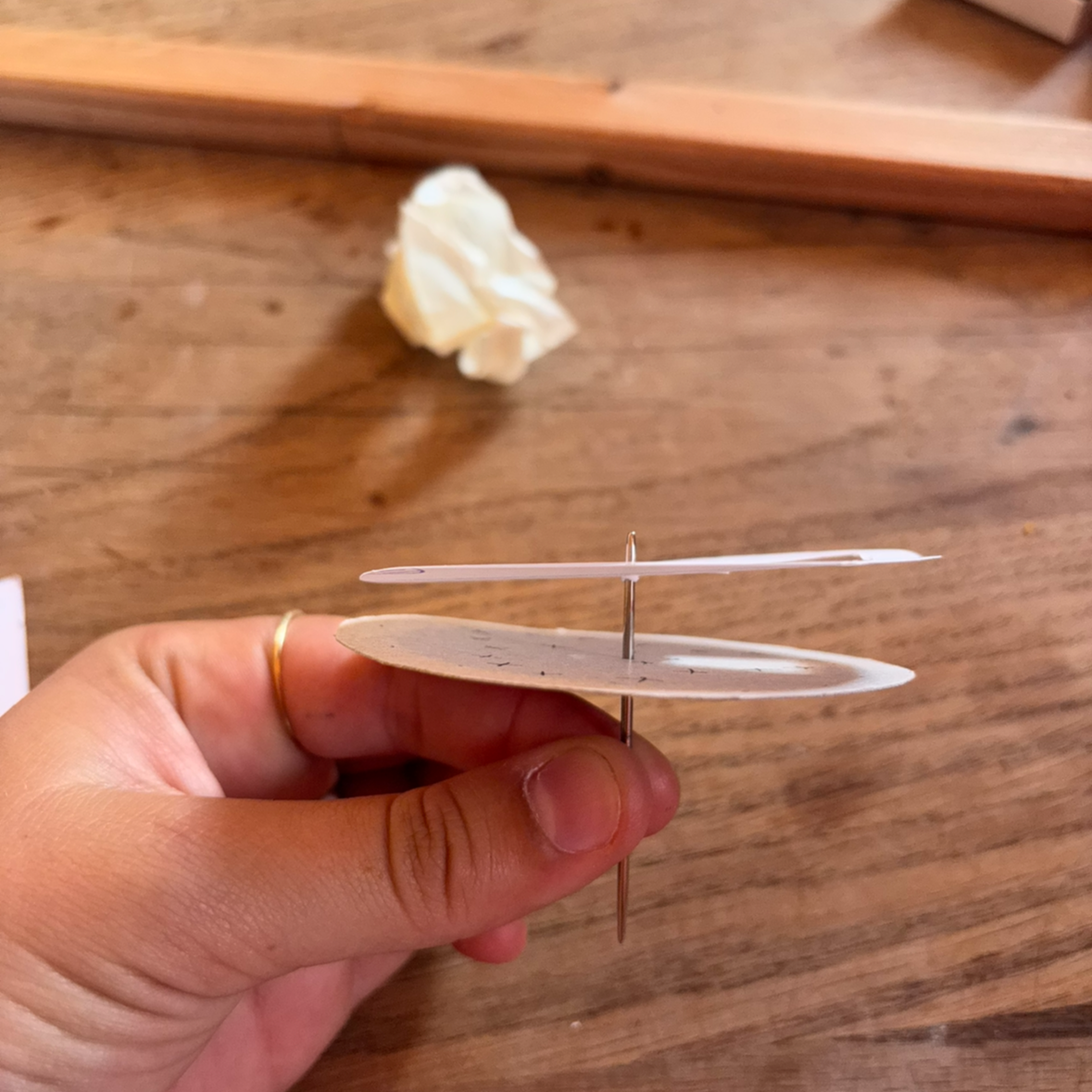

A first test of my wave mechanism worked best as a horizontal piece, seen from above. To bring the wave vertical, I drew on my animation background and explored how to “animate” a flat surface in the physical world. The result is simple: twelve wooden planks hang from threads, their other ends fixed to a rotating latch on a small motor. As the latch turns, it pulls each thread in sequence and creates the illusion of a moving wave.

I like how the circle with the latch recalls the clock we are so familiar with. Since I want to use the circatidial rhythm for this installation, the mechanism inspired a new idea: a tidal wave that reveals and conceals parts of the work.

Testmodel Kinetic Wave II

WIP of a model made of wood (a bit sturdier material than cardboard). A small motor drives the pointer. Next challenge: I have to find a way to attach the threads to the tip and still be able to rotate freely.

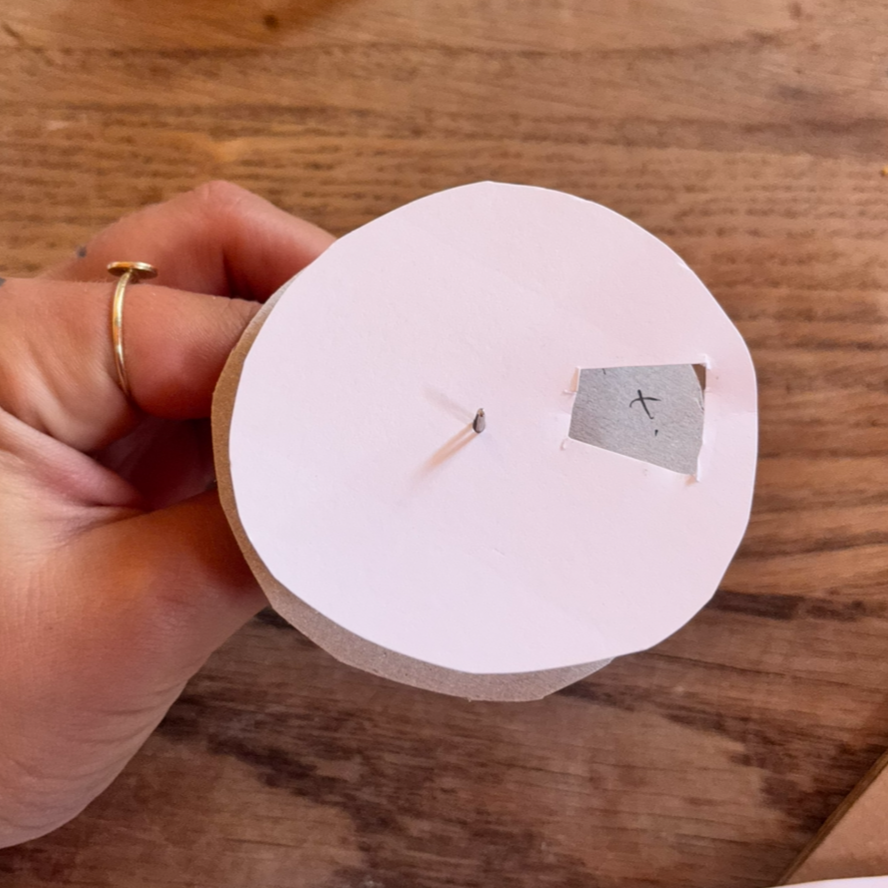

Testing the new bottle-cap-tip with threads and screws to keep tension on the threads, and IT WORKS. I have to admid that I’ve reached a point in this project where I’m balancing between ‘I have no idea what I’m doing’ and ‘this could actually work’.

When testing that previous model I'd found that the pointer was too flexible. So I made a new one of wood and fixed it on the motor axis. I also replaced the spinning tip. For that, I used a bottle cap that I found on the beach earlier today, drilled tiny holes in the sides to attach the threads.

And after testing this mechanism over and over again, until it finally worked, I realised that I was building a machine. A machine that visualises the movement of the tides, triggered by real-time water data. Not a machine built to speed things up, but one that reveals the slowness of the tidal cycle. You have to observe it for six hours to witness a single wave passing by.

The machine became the ultimate symbol of progress during the Industrial Revolution. For centuries, muscle, wind, and water had powered human life, but steam engines, factories, and later electricity took over. This brought unprecedented growth and prosperity, yet also a hidden cost: massive burning of fossil fuels and an accelerating wave of pollution and emissions. The machine that once promised liberation from labor is now deeply entangled in today’s climate crisis.

The machine has long been the emblem of human progress: created to accelerate, to make us more productive, to bend time to our will. Precisely because of this symbolism, I began to wonder what would happen if a machine did the opposite. What if, instead of speeding up, it slowed us down? This thought opened the way to machines that do not dominate nature, but translate its rhythms into the familiar language of technology so that we might see, feel, and understand what usually remains hidden.

The tides themselves behave like a stage curtain: opening and closing with each cycle. At high tide the curtain is drawn, the water covers the stage, and what lies beneath remains hidden. At low tide the curtain slowly opens, revealing the full landscape; mudflats, birds, seals, traces of life that moments before were invisible. My wave machine mirrors this movement. It acts as a kinetic curtain: closed in one moment, expansive in the next.

And that brought me to a new idea: to see the Wadden Sea, with its tides, as a theater. The tidal wave itself becomes the curtain; opening and closing, concealing and revealing, and at the same time the director that sets the rhythm of the play. I can watch the tidal landscape for hours without a moment of boredom; like a slow, endless film. This principle forms the basis of my installation: a kinetic theater made of machines that imitate natural elements and translate them into human language: technology. Together they perform a landscape drama, a theater played with and by the environment, constantly responding to the forces of nature.

Machines

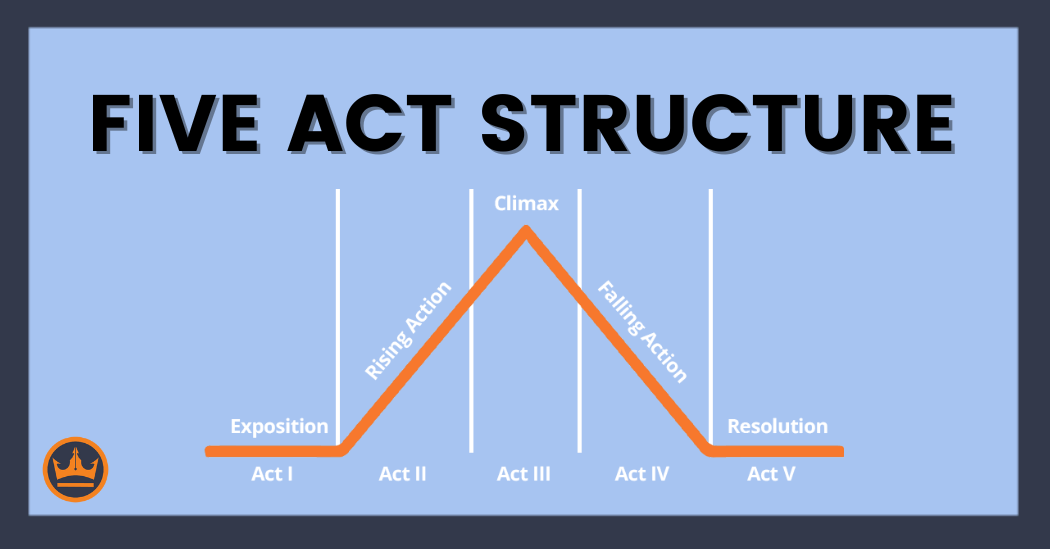

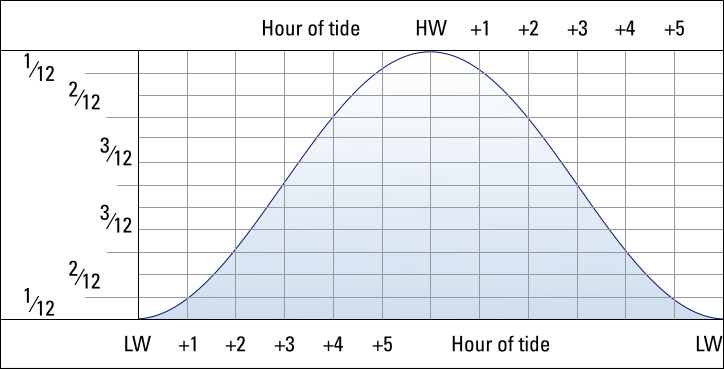

From (puppet)theatre, I knew the classical five-act structure: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. When I placed this alongside the tidal curve, I realised how closely they mirror each other. Both follow the same arc of tension and release. By merging these two worlds, I found the basis for the Kinetic Wadden Theater: a landscape unfolding like a play, directed by the tide and the elements.

Organisms, The Elements, Processes

In this kinetic theatre, I want to use machines as puppets: not as efficient devices, but figures that translate natural rhythms and invite the viewer to slow down.

Inspired by biomimicry, they visualize the movements of living organisms, natural processes and forces. Like a puppet comes to life through breath and movement, these machines seem to breathe and respond to their surroundings.

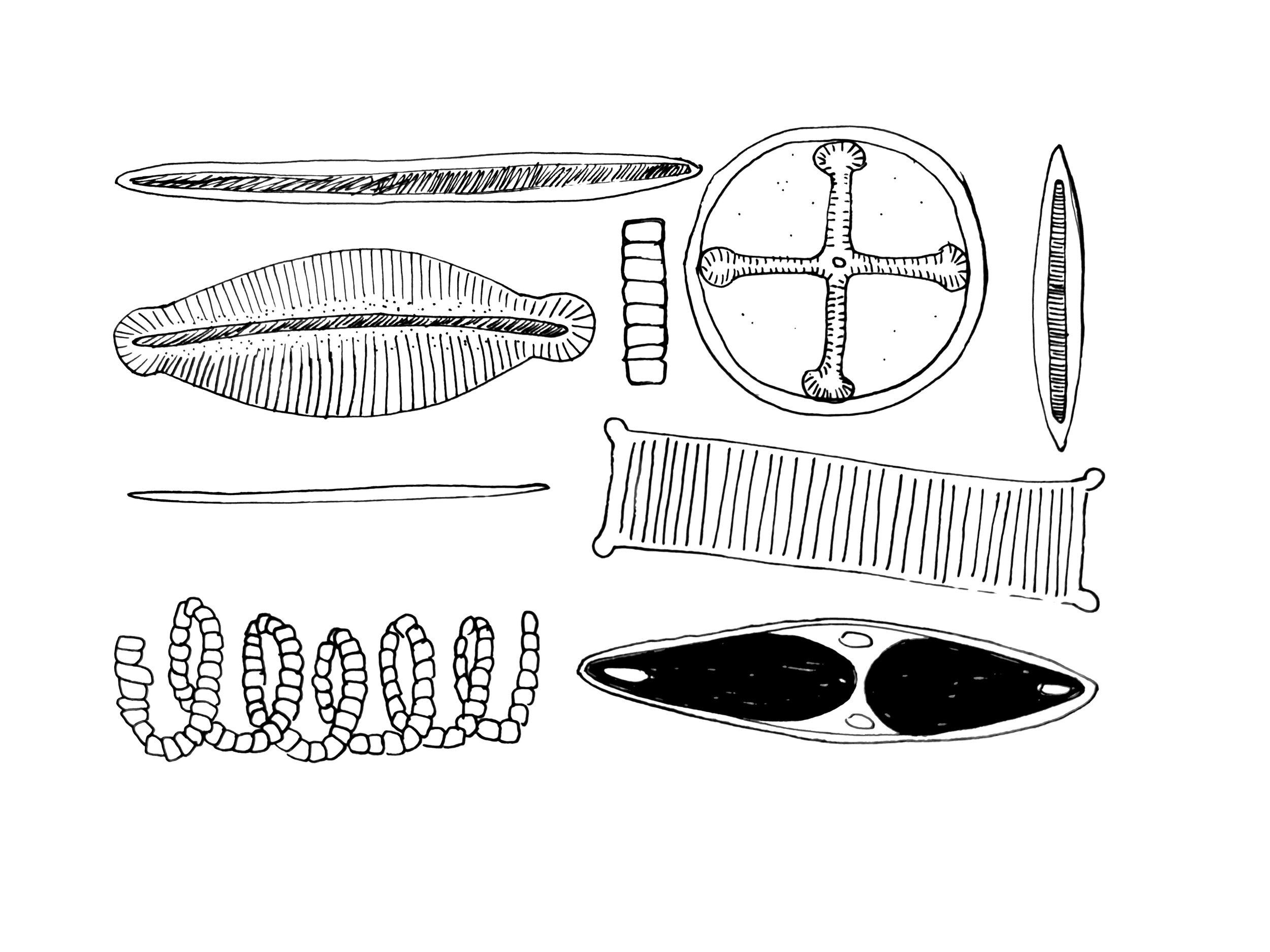

Now lets talk about Diatoms

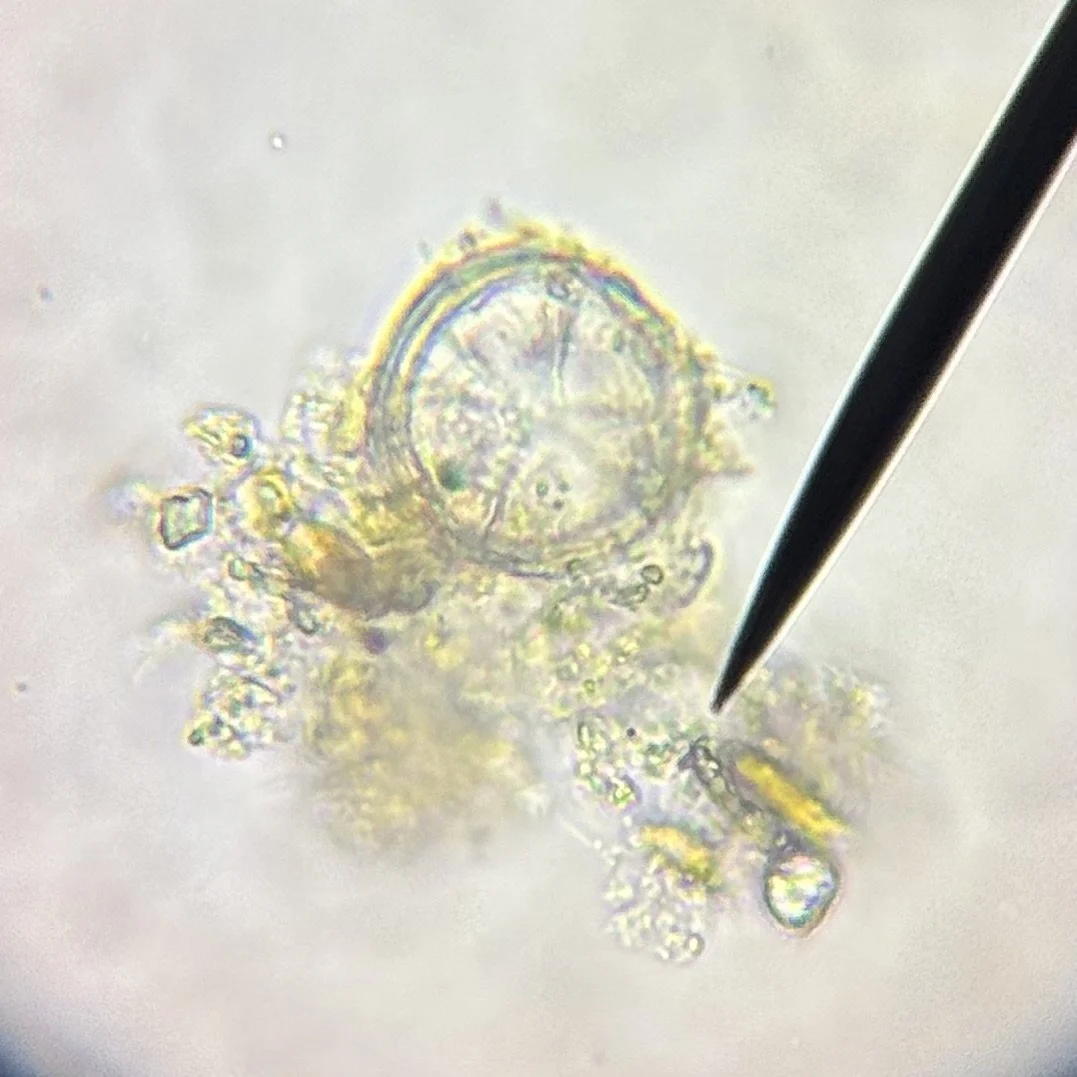

Diatoms are microscopic, single-celled algae with glass-like shells made of silica. They are among the smallest organisms on earth, yet they play an enormous role: through photosynthesis they produce about one-fifth of the world’s oxygen; every fifth breath we take. Their intricate geometric forms, like circles, stars, and rays, make them both scientifically vital and visually mesmerizing. Sensitive to environmental changes, diatoms are also key indicators of climate and water quality.

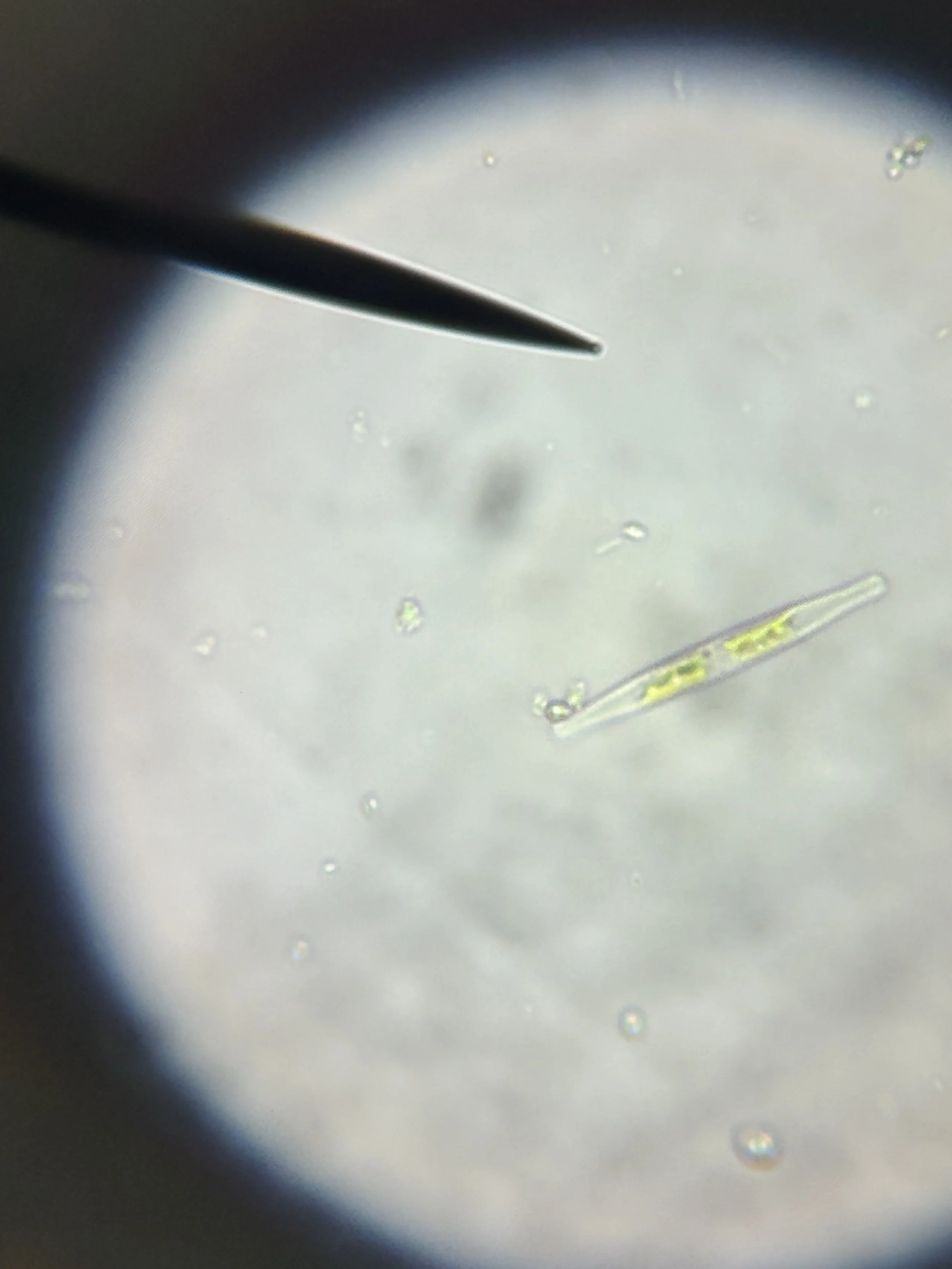

And because I always want to see, do, make, and experience everything myself, I wasn’t satisfied with just looking at pictures of diatoms… So I went out to find them myself. The school De Jutter was kind enough to lend me a microscope, and my new mission could begin: searching for diatoms. I collected a few water samples and made my own slides (something I hadn’t done since high school biology, so it was a bit of trial and error), but it worked!

I found several diatoms in my preparations. WOW!

Fieldwork Log – Low Tide Sampling

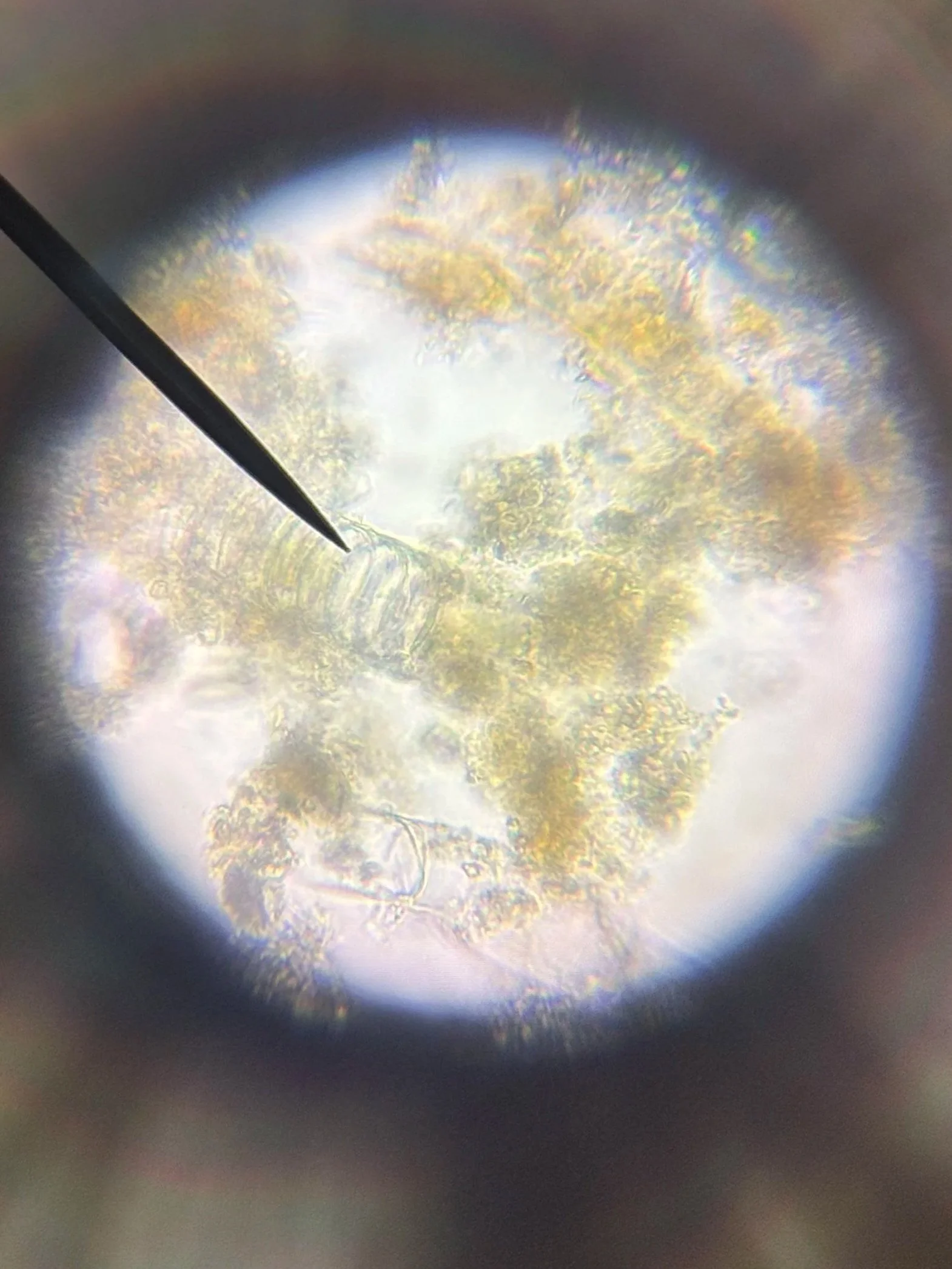

Collected samples from tidal flats during low tide, focusing on the thin brown surface film. Microscopic examination revealed a very high abundance of diatoms. Unlike previous samples, no searching was required; diatoms were present in large numbers across the entire field of view.

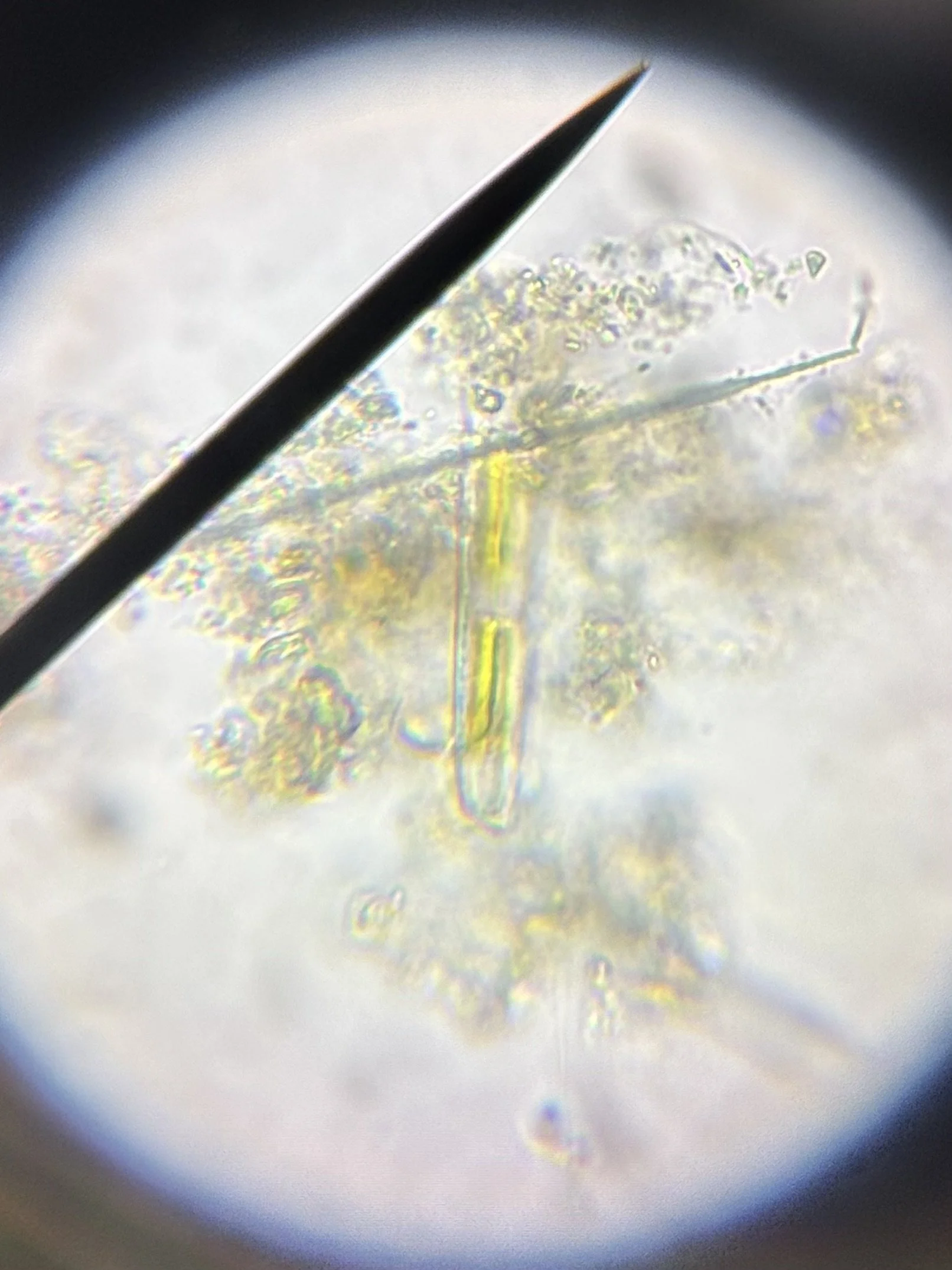

In this sample, a long, tube-shaped diatom was clearly visible. The cell appeared to be built from a series of fine, regular cross-bands, giving it a ringed structure. The diatom was partly embedded in clumps of organic material, but its rhythmic pattern made it stand out clearly. It is most likely a chain-forming species, where multiple cells remain connected in a row, forming a filament-like strand.

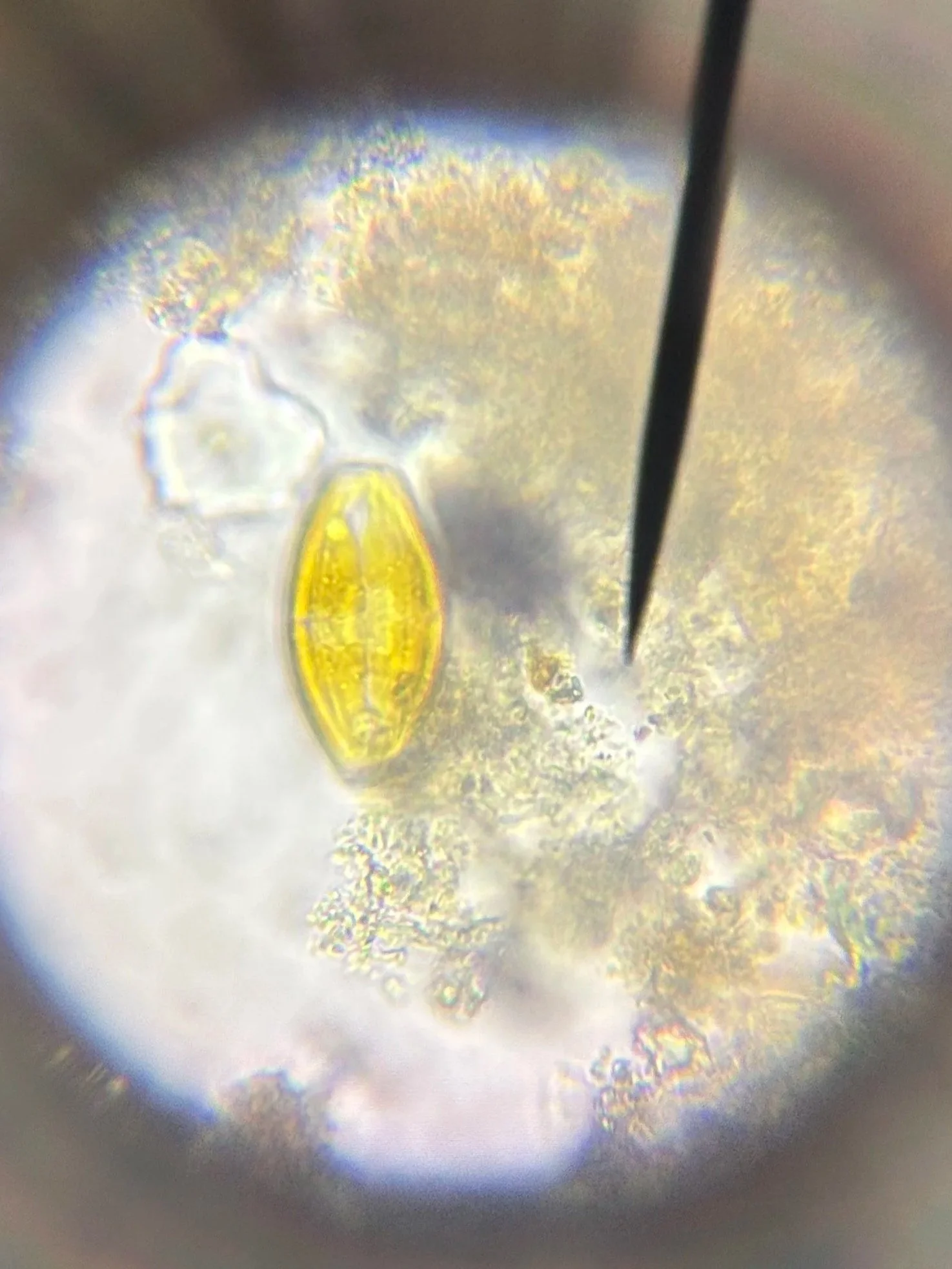

Another diatom in the sample had a clear boat-like shape, with fine lines etched along its silica wall and a slight central thickening. Its golden-brown pigments filled the cell, giving it a warm glow under the microscope. Nearby, a much smaller, lens-shaped diatom was visible.

What fascinates me about these microscopic organisms is how something so small can have such a profound impact on its surroundings.

I carried out a test using coloured acrylic glass. In my experiment, sunlight passed through the coloured glass, casting reflections that revealed something unexpected: every relief, scratch, or imperfection in the surface became visible in the reflection.

Just like diatoms, the material needs sunlight to come alive. Without it, the glass remains silent and transparent; but as soon as the sun touches it, patterns begin to appear.

This observation opens up the possibility of using the glass in a light-responsive machine, a structure that reacts to sunlight and reveals images through reflections that are larger than itself, constantly changing with the conditions of the sun.

From diatoms to light reflections

My research into diatoms set me on a new path. In their fragile glass shells, these organisms turn light into life. Drawing from that, I started working with glass and reflections with the sun.

While developing the first light-driven animation machine, I discovered something essential: the sun literally created a film that existed only in that moment, in that exact place. A film without a camera, directed by nature itself. This became the foundation for this project: a nature film that cannot be recorded or repeated, but continually recreates itself.

Testmodel I

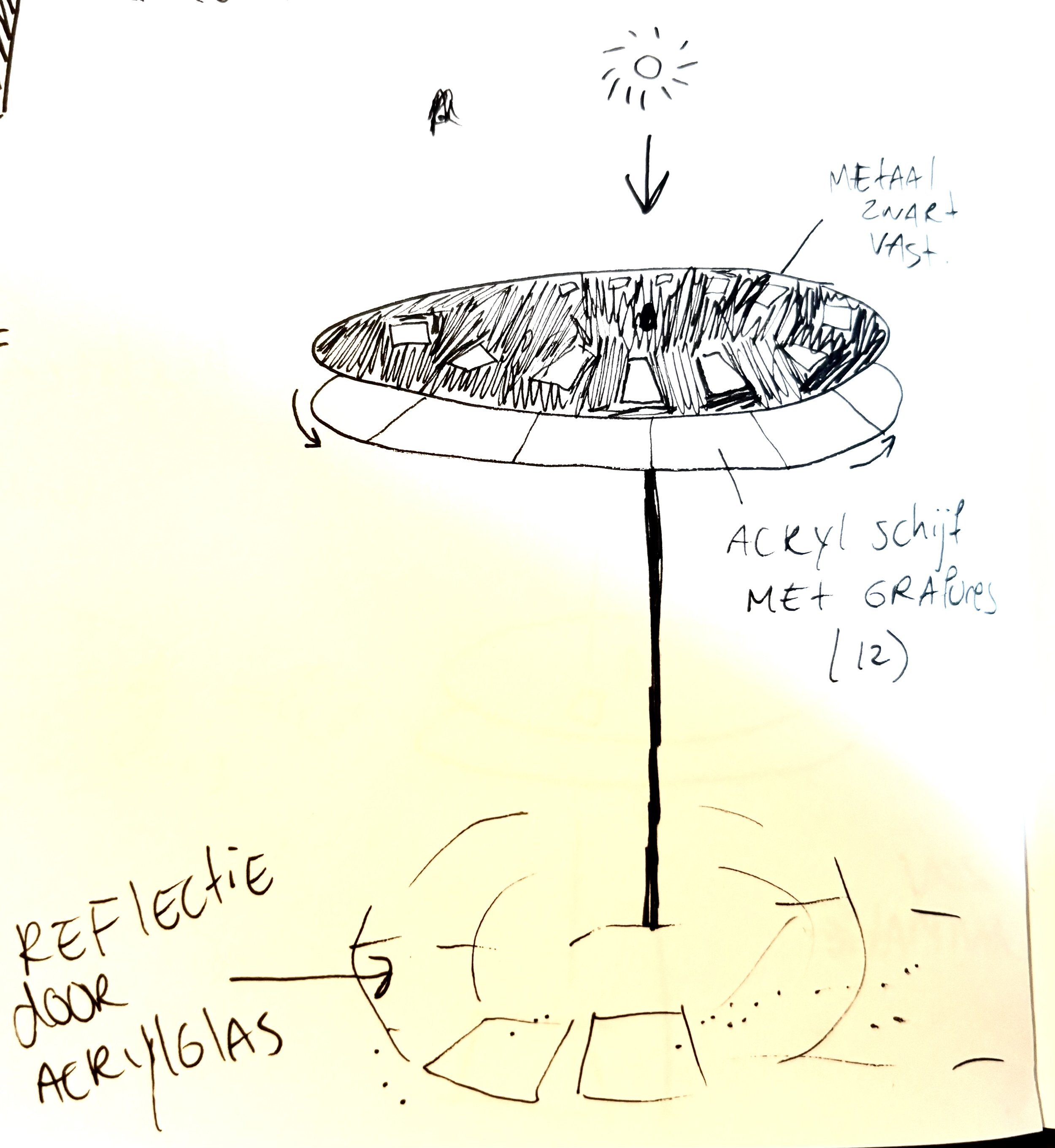

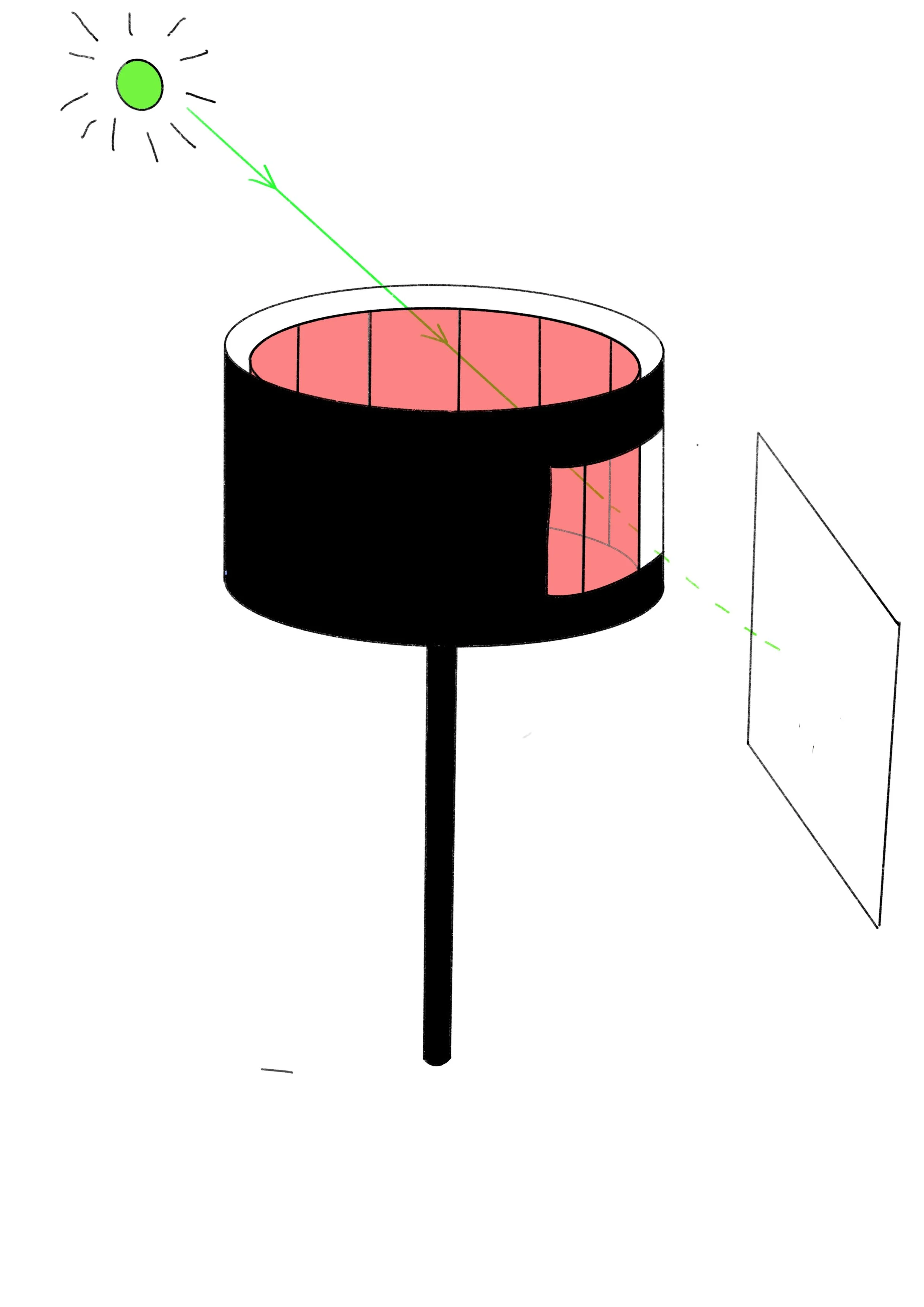

My first experiment was with a traditional zoetrope, using upright acrylic plates arranged in a circle. When the structure rotated, the engraved drawings came to life as moving images; a mechanical animation powered by light and motion.

But the problem with this model is that it only works when the sun shines through the machine from a specific angle (which only lasts a short time)

Testmodel II

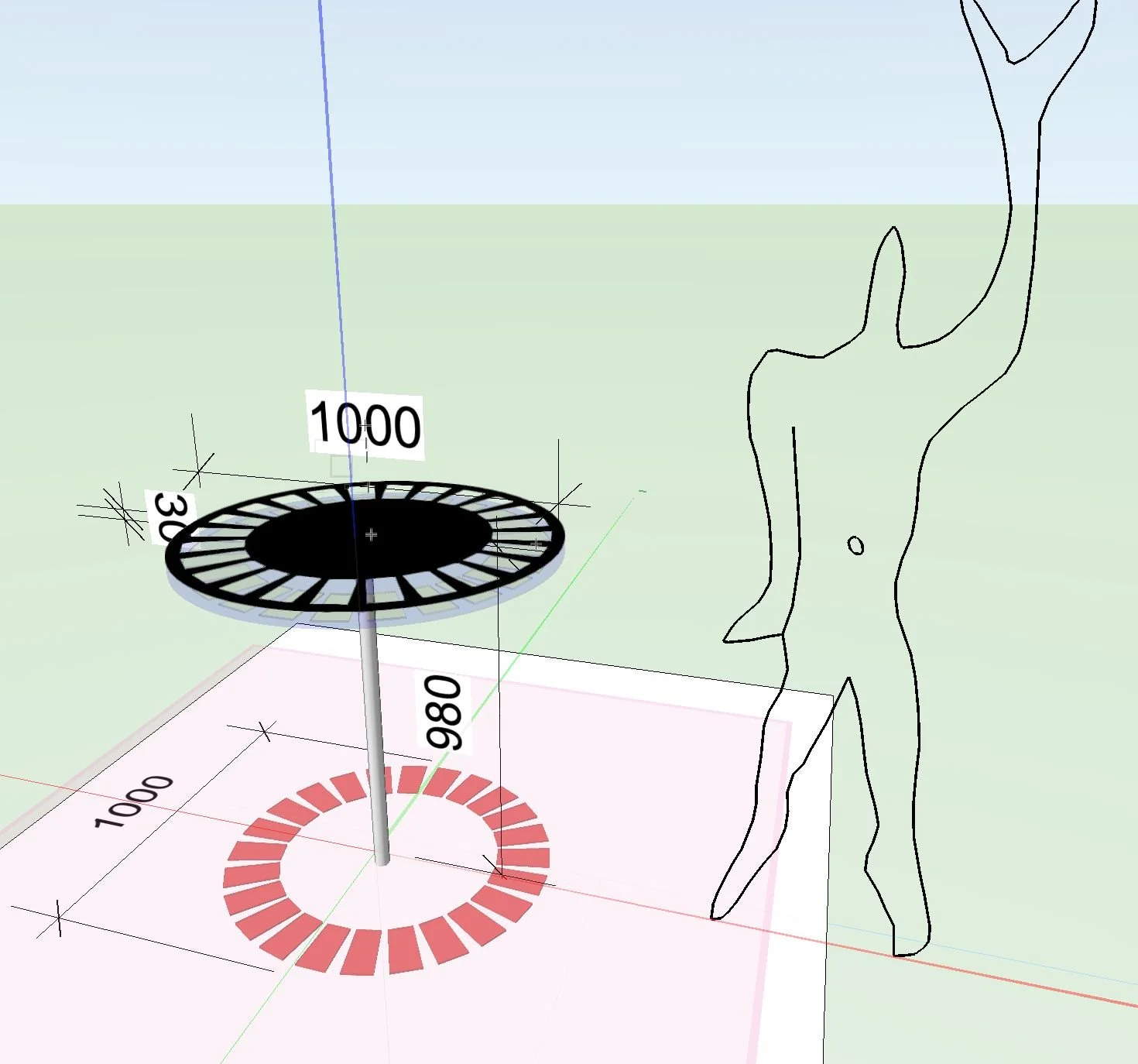

From there, I developed a horizontal version. In this model, the acrylic disk lies flat beneath a fixed metal plate with a single square opening. As the disk slowly turns, sunlight passes through the opening, projecting each engraving onto the ground as a shifting reflection. Powered entirely by the sun, the work transforms light into motion, much like diatoms transform sunlight into oxygen.

Design

The top disk will be made of steel with cut-out ‘frames’, while the acrylic disk will be engraved with 24 drawings. This arrangement will create a stroboscopic animation when the acrylic disk rotates beneath the fixed metal layer. The animation becomes visible in the reflection of the colored acrylic when sunlight passes through the openings in the metal disk.

After testing the previous model, I realized that achieving a smooth perception of the animation requires a stroboscopic effect. This led me to revisit traditional animation devices, such as the zoetrope, and adjust my design accordingly.

A quick test with an ultrasonic sensor that activates a motor when movement is detected within a specific range. I will use this principle to set the acrylic disk in motion: when a visitor approaches the machine, it comes to life. In this way, human presence, together with sunlight, activates the film.

I’m exploring how this motion can take shape in material. This led me to bimetal; a metal that changes shape with heat, and returns to its original shape when it cools down.

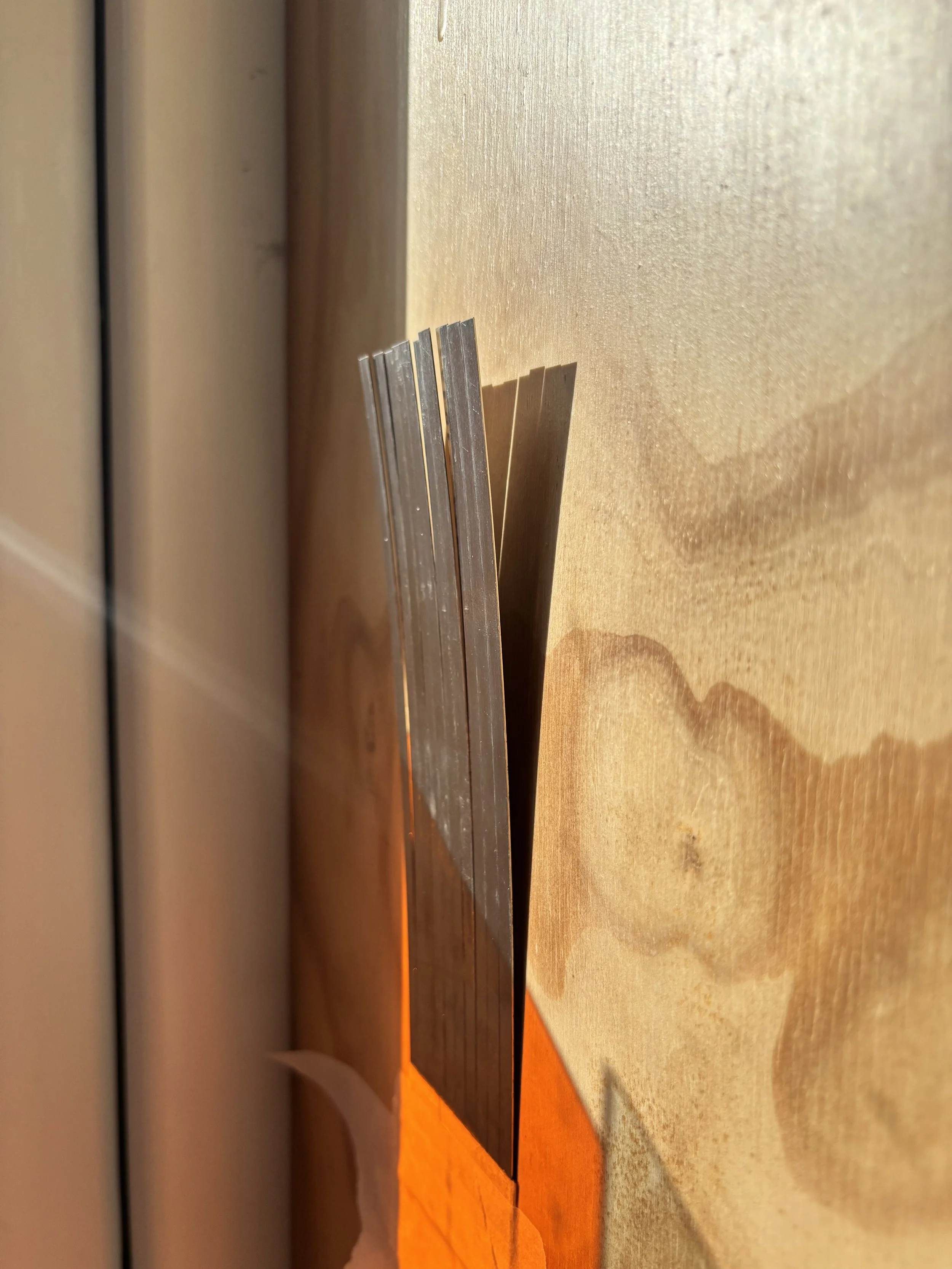

The bimetal strips were placed against a sunlit wall and taped at the bottom. As the sunlight reached them, a noticeable bending appeared within a few minutes. After about ten minutes, the bending had roughly doubled.

a timelapse shows the bending over 1 minute of solar exposure

after 1 minute of solar exposure

This bimetal strip is commonly used in thermostats. I will experiment with the amount of heat required to bend the strip at different angles. I’m also exploring the use of larger sheets to increase the surface area and capture more sunlight.

after 10 minutes of solar exposure